Born in Turin and based in Athens, artist and curator Paolo Colombo has held posts at the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art, the Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XXI Secolo in Rome and the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva and was the first European artist to exhibit at PS1 in New York. Resuming his artistic practice in 2007 after a twenty-one year hiatus, Colombo returned to his beloved paper, pencil and watercolours, materials he values for their refusal to ‘allow for corrections’. Incorporating poetry and geometry for structure and embellishment, his works comprise abstract histories that traverse antiquity and modernity. The concept of a linear passage of time is one challenged by both Colombo and writer Yasmine Seale in their respective practices, with Seale’s own focus being on Arabic literature, translating ancient pieces for contemporary audiences, allowing new readers to jump back and forth along the time-space continuum. Here, they come together for a candid conversation on mark-making, night-walking and time travel.

Paolo Colombo: On Land/At Sea has a strange correspondence with a print you made a little while ago, the text of which says: ‘all / that is on the land, in comparison with what is in the sea, is // loud / smoke’.

Land and sea are a steady thought; the shorter the verses, the wider is our sense of the expanse. The first image that comes to my mind is one of calm black waters and a starry sky, with the slight sound of water and no moon.

Yasmine Seale: A steady thought, and at the same time a field of illusions and metamorphosis. I recently saw a breathtaking object at the Asia Society here in New York: an embroidered screen made in Japan in 1915. Silvery waves roll across its four panels, set in a lacquered wood frame. Screens painted with seascapes had existed since the Tang dynasty in China and were sometimes placed in bedrooms to aid relaxation. This screen, at first sight, appeared to be painted. It was photorealistic, uncanny. Even standing in front of it, you couldn’t believe it wasn’t painted. Even after knowing how it was made. To see the silk threads – 250 shades of blue and grey thread – you had to stand so close that you set off the alarm. So to look at this screen was to hang between consciousness and fantasy, a nocturnal state. Your paintings play similarly with illusion, but in the opposite way: they seem to be woven. Their dreamlike effect washes away the immense labour and care that surely goes into them.

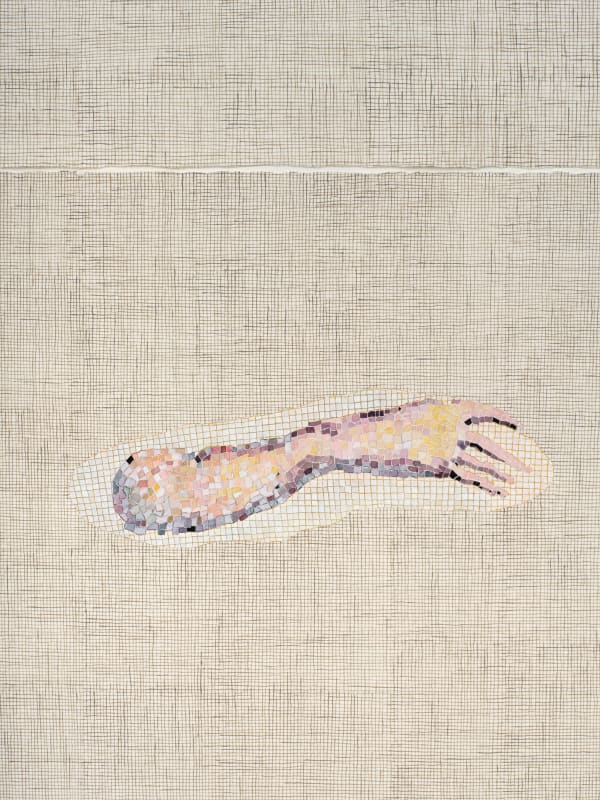

Paolo: In a way, embroidery suggests the weaving of time, because time is so inherent in this form of art. Embroidery has absolute proximity to the artist’s hand. In fact, weavers constantly touch their work, like potters and ceramicists do. When I work, I often represent the weave of organza or tulle, painting freehand the warp and the weft of the fabric. I touch the sheets of paper on which I paint with my right hand, as I hold it down with my left hand.

Time is embedded in my work. Long hours echo the hours Penelope spent weaving during the day, to undo her canvas during the night. She pretended to weave a canvas to honour her father-in-law, Laertes. This canvas is at the core of the Odyssey; it is the shape of a deceit not unlike that of the wooden horse.

As you say, it is a field of illusion and metamorphosis.

Truth is, I have a fascination for work done by hand, for lonely work done in silence.

In 1979 I was employed for nine months in a frontistirio – a private night school – teach- ing Italian. My schedule was eight pm to midnight. I returned home at night from the end of Patission to my flat below the Acropolis. A long walk. The nights were perfumed, and the city was empty. On my way home, I passed a small store not more than six square meters, where a man in his seventies sat behind a small wooden desk. He was thin, with sparse hair and hollow cheeks. He repaired watches. This image stayed with me for many years, and I so imagined his nights and life:

The Man Who Repairs Watches

Black for night

grey for dawn.

In Athens:

watches sweeping

at each swing

of the balance wheel.

I lead a negligible life.

(No, no,

it was not always so).

My mother once told me that:

I was born

with my hair

already parted on the side.

[in summer,

in slumber]

that is:

In summer

in sleep

my neck sweats on the pillow.

In sleep

my spirit

(just a mouse)

furtively slips from my mouth.

Yes:

sleep,

slumber,

mice,

and a balance wheel.

Yasmine: I’m fascinated by the story of Penelope, weaving by day and unravelling her work at night. Because it is a shroud she is weaving, this unmaking is also a way to keep death at bay. A ruse against finality, like Shahrazad weaving stories to delay her own death. And because these gestures are tricks, as you say, they have often been read in terms of craftiness, the wiles of women, and so on. But it’s also the dream of all artists, isn’t it, this effort to stop time? Or better: to thicken it, give form to the constant elapsing. To dwell in perpetual making: a kind of paradise. To live in the layers, as Stanley Kunitz writes in a poem called ‘The Layers’: ‘I am not done with my changes’.

(I was dazzled to learn recently that the timekeeping mechanism in old clocks is called the escapement.)

Your latticework, the tracing of warp and weft, gives these drawings an uncanny sense of depth. We feel disoriented, deliciously caught between scales. Like looking at a galaxy through a microscope. The handmade grids are slightly irregular, and these accidents are what create texture and movement – and wit. They also remind us that paper is a kind of textile. They remember the plant life it contains, the organism it once was. They are subtle, in the oldest sense. The word originally meant ‘finely woven’ and is from a root meaning both to weave and to fabricate. Mark-making and night-walking activate the ancient beauty of ancient gestures. I’m struck by how your images belong to the age we live in and are at the same time in dialogue with ageless elements, with antiquity. The mermaids are your contemporaries.

Paolo: You opened so many doors; I will try to walk into each one.

I began to paint when I was nineteen, a few months after my father passed in April of 1969. After his passing, in a dream he told me that I would die on August 9. I had just begun my first skin and fog drawing, a large page covered with hundreds of thousands of systematic pencil dots over a greyish wash, to mimic pores and fog. I slowed my work in order to finish it past the date of August 9, wagering that death would not take me if I hadn’t finished my drawing. It didn’t. In a very primitive way I kept fate at bay with the ruse of art.

In my reading of the Odyssey, I sensed Homer felt admiration and empathy for Penelope. One of the cornerstone books in my library is Trickster Makes This World by Lewis Hyde. Hyde looks at the mythical figure of the Trickster (among them Hermes, Coyote, Krishna) and how each one through his unpredictable behaviour breaks boundaries and sets the wheel of the world in motion. The poem by Kunitz is so appropriate to the changes that are one’s life.

I am sincerely touched by your words. My paintings are watercolours that often represent a fabric – organza, tulle – on which words are painted like an embroidery. They are poems I write. They generally are short – short enough for me to know them by heart. I edit them in my mind before I write them on paper. The process is not so different from the way I approach painting. Often months go by before I begin. The passing of time is embedded in my work, in the conception and in the making. Time most compressed: the work of months becomes real in a few seconds for the viewer and the reader. The lines of the fabric take weeks to paint; their purpose, like that of a veil, is to reveal and to hide. Beyond the fabric is a dark hued watercolour wash, most likely the night or the sea.

Yasmine: It’s funny that you mention Trickster Makes This World. I taught it last summer as part of a class on One Thousand and One Nights, which is full of tricksters, and especially the figure of Sindbad. The trickster, Hyde writes, is ‘the spirit of the road at dusk, the one that leads from one town to another and belongs to neither’. And it seems to me that this dusky in-between is a fertile space for you, as someone who lives and works at the juncture of several places, epochs, languages, forms.

I am also thinking of Anselm Kiefer’s small artist’s book, Die berühmten Orden der Nacht (the title is from a poem by Ingeborg Bachmann about the beauty of life under the sun, ‘much more beautiful than the celebrated orders of night, the moon and the stars’). It shifts from photography to painting, from day to night, from sunflowers to stars. The final pages are made of heavy card-stock thickly layered with black paint and splattered with specks of white. The infinite variations of the night sky.

Unlike Kiefer’s, however, your night is full of subtle colours – not darkness but a more mysterious brightness. The words WAX / WANE / EBB / NEAP refer to the tides of the sea and lunar cycles. Fragments of a calendar governed by the moon rather than the sun, a conception of time that is cyclical rather than linear perhaps. And with this series of works, you appear to be returning in some way to those first slow, meticulous drawings. What draws you to repeat those gestures you first made at nineteen? What is different this time?

Paolo: There might not be a difference, just the lasting pleasure and necessity of sitting at a table for a day’s (night’s) work. If time is cyclical – as I do wish – I welcome feelings appearing at different stages of one’s life. More than fifty years ago – yet with the clarity of last night – in a small terrace under the moon I took a knife and separated a watercolour from the pad it was attached to. It was the first gesture of so many I would repeat for years thereafter.

I remember that I had read that evening the poem ‘Helen’ by George Seferis, the first line of which says: ‘The nightingales won’t let you sleep in Platres.’

It is still my favourite poetic incipit ever. There are moments that split time in two: so many beginnings in the batting of a lash, under the spell of words and darkness.

The hope of a night of longing was ever present. There was a true blessing in being nineteen years old, free and under the moon.

I do not live in the North. In my geography, the hour of panic – literally, the hour of Pan – is at noon, when the sun is brightest and hottest. (According to Ovid, Pan roamed the hills of Attica and of the island of Pelops, now the Peloponnese, pursuing pleasure and playing the flute, an instrument that originally had been the nymph Syrinx, transformed into an object to protect her from Pan’s sexual ardour). Here, fear, folly and furor are attributes of the day; the night comes with sweetness and slight melancholy.

The night fosters images – images and song, as Kenneth Koch would describe poetry. These can only be replicated in a drawing or in a verse, because they would not hold true in narrative and in prose.

I wrote a brief poem about the night, two verses with a precise image in time and place. I hope it conjures the picture of women whispering, of benevolent affinities, of secrets shared, and of shadows and dimness.

At night the blind women of Athens mend clothes and speak of angels.