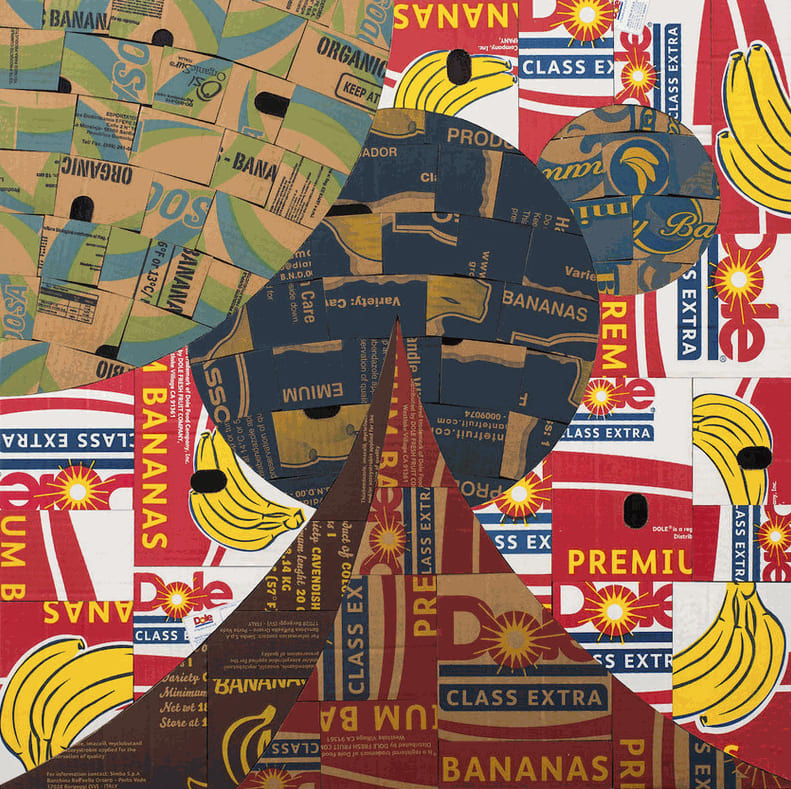

Jebila Okongwu critiques stereotypes of Africa and African identity and repurposes them as counter-strategies, drawing on African history, symbolism, and spirituality. One of his preferred materials is banana boxes; their tropicalized graphics articulate an ‘exotic’ provenance, much like the exoticization of African bodies from an ethnocentric perspective. When these boxes are shipped to the West from Africa, the Caribbean, and South America, old routes of slavery are retraced, accentuating existing patterns of migration, trade, and exploitation.

Born in London and then raised in Nigeria and Australia, Okongwu currently lives and works in Rome.

Recently the Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum Linz, acquired his Divination Painting (Exotic Dawn).

CB: How are you changing the world with your art?

JO: It would be nice to think that my art was changing the world, but I have never had that intention. If I did, I would have perhaps chosen to be an activist, a scientist, or work in a profession in which I could achieve direct change. Nonetheless, I would be pleased if my art was effective in inspiring progressive thinking by its examination of sociopolitical issues. The stimulation of discussion and awareness around certain themes can often contribute to conditions which lead to positive change.

CB: Why have you decided to live in Rome? How does the city create opportunities for you?

JO: I did not actually make a committed decision to live in Rome, it’s something that just happened. After finishing my studies in Painting at the University of Melbourne, I felt the necessity to travel, confront myself with a different culture, and to see the masterpieces of art history I had studied at art school. One thing led to another, and the city seemed to create the right environment for me. Rome has a very slow pace, which could seem disadvantageous for a contemporary artist, but it is generous and nurturing and doesn’t force you to develop an artistic identity overnight as can be the case in other international cities. I have also had the experience of living in New York City, and even though it was fast paced and stimulating, I felt the anxiety of being expected to perform as a professional and exhibiting artist. This can be detrimental for an emerging artist who is still searching for their voice.

CB: Tell us about your artistic research.

JO: I am a multidisciplinary artist and I draw on my African and European heritage to articulate the experience of living between two cultures. My consciousness has been formed by cultural, social, and artistic values which often reflect divergent realities, so a lot of my research is dedicated to the reconciliation of some of the conflicting elements which make up my identity, and which I also see reflected in the world.

In some of my recent work I have been investigating methods to communicate what it feels like to be embedded in structures of domination such as colonialism, racism and exploitation, and how to represent this aspect of blackness. I have been experimenting with imagery related to BDSM, not in an attempt to allude to the histories of domination and oppression by analogy with these practices, where acts of submission are obviously voluntary, but as an instrument to examine roles of difference and the embodiment of certain types of sensations. I am examining how difference becomes material within the contexts of race and power, and am attempting to articulate the complex histories of physical experience on the body of the other, where domination and brutality have not only been profitable, but also eroticized.

CB: In what way are current events a source of inspiration for you?

JO: I am very much inspired by global current events but never attempt to depict or refer to them in a literal way. Specific events often give rise to strong social reactions, but they also belong to a distinct time and place, and are therefore somewhat fragmentary. I am not negating their importance, but they need to be considered within a larger context. Think of the individual details which are embroidered into a decorated tapestry – I am much more interested in the nature of the tapestry as a whole. As current events become assimilated into my consciousness, I try to articulate the essence of what they mean and what makes them resonate so deeply within the psyche. I think about ways to represent the underlying mechanisms of history, politics, and economics which drive them. In turn, these are tempered by the associations, sensations, and emotions that I feel at a personal level.

CB: I agree with an article written by Annie Olaloku-Teriba in Frieze entitled “Toppling Statues Is Not About History, It’s About the Present” (and how we want live in the future). 2020 was a very difficult year, but something very important has begun to actively contrast racial injustice. The intense Black Lives Matter protests, have reignited a debate about what historic public art should commemorate. This issue of public art is very important, what do you think about it?

JO: It has been crucial to create this juncture with historic and commemorative public art, and I also agree, the toppling of statues has now created new opportunities and directions for the future. The current problem is to form some sort of consensus on what the new public art should be. I dream of a future in which public art will no longer induce politicized reactions, only at this point it can be successful. The true nature of living on this earth is surely not to be politicized, it is just ‘to be’, and this is especially important in public spaces. Unfortunately, it is still necessary to be politicized because we live in a world where people’s basic human rights are not respected, and it is unsafe for some of us to even go out on the street.

CB: How can we displace the Renaissance construction of Man to transform our scale of thinking from regional parochialism to the planetary?

JO: I like your term “planetary” because it suggests a kind of cosmic transcendence and I think that this is where we can find the answer.

There are two different ways of thinking which I try and reconcile in my art. Firstly, the one you mention of the Renaissance ideals of Humanism; these led to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, and promoted a secular view of reality – a cosmos which is best understood by reason and scientific knowledge.

Secondly, we have the knowledge of “tribal” cultures; these have always understood that the cosmos is sentient and has its own systems of communication. Reality is multi dimensional and incorporates legends, myths, ancestors, spirits and gods.

I am equally inspired by both kinds of thinking and look for parallels and points of connection between the two. Perhaps we need to transcend the idea that one way of thinking needs to displace the other, maybe it makes more sense to identify and develop domains which are common to both.

CB: Édouard Glissant’s masterpiece, Poetics of Relation, examines how humans have come together, often in extreme circumstances, to create new worlds, new forms of relations, new poetics, and new visions. How can we create a just new world? How can we create new visions?

JO:One of the ways in which I have been researching methods to depict the new world you are talking about is by investigating cultural and technological ideas related to humanity’s experience of the cosmos, and perhaps the best way to answer your question is by giving you some examples:

In my drawing “Portal to a Multi-dimensional Reality”, 2014, I depict an idea for a project which would be developed with an astrophysicist, and by using relatively simple scientific instruments. A functioning radio telescope, sculpted from banana boxes and reinforced with fiberglass, would detect the cosmic radio waves which stream down to us from the edge of the universe. This data would be computer elaborated into geometric forms based on the visual languages of traditional Nigerian Igbo wood carving and Uli motifs. Paintings would then be created, and they would contain information that has literally come from the very limits of our current systems of belief and understanding.

My “Cosmic Mediation” series, began in 2014, depicts compositions of celestial bodies coming into alignment above temples. The geometries in the image, again informed by Nigerian Igbo carving, are intended to signify the truth of cosmic perfection. Human apprehension of the cosmos leads to states of objectivity and collectivity, after which tensions caused by differences between race, ideologies, and religions, etc, begin to seem very trivial.

In my series of “Divination Paintings”, I endeavor to engage with the multi-dimensional realities of traditional African art. I randomly apply triangles of printed banana box cardboard onto canvas, which results in a field of broken down graphic elements, yet simultaneously reveals new visual structures. No longer in control of the image, I take on a role similar to that of the diviner or shaman. I attempt to transcend my own ego by relaying coded information, and possible revelations, from a sentient cosmos. The collages are often transposed into oil paintings, which allows me to create works of larger scale and to accentuate the graphic forms.

So in these three examples, you can see how I have identified prototypical images and themes related to the Cosmos in the art and technology of diverse cultures, and then assimilated them into my own artistic practice. Given that the cosmos is an element of our existence that is truly universal regardless of culture, time or place, I believe that this is the type of research which can lead us towards the creation of global empathy and collective identity. To create the just new world and new visions that you talk about, we need to investigate the transcendent experiences which are common to all of humanity.